Who would think growing vegetables could get you into trouble with the law?

Well if certain agribusiness interests have their way it will no longer be legal to save seeds from your plants and share them with other people. In order to protect their business interests international agribusiness companies are lobbying for regulations that require every seed sold to be nationally registered, a process that is both expensive (about 1500 euro per seed type) and cumbersome for small seed producers.

First, what are heirloom varieties?

It is generally accepted that an heirloom vegetable is an old cultivar that is “still maintained by gardeners and farmers particularly in isolated or ethnic communities.” A cultivar is a plant or grouping of plants selected for desirable characteristics that can be maintained by propagation. The world’s agricultural food crops are almost exclusively cultivars that have been selected for characteristics such as improved yield, flavour, and resistance to disease.

(wikipedia)

(wikipedia)

Heirloom plants are deemed to be “open pollinated” which means they are pollinated by natural means, such as birds, wind or insects. Heirloom seeds will “breed true” and produce plants roughly identical to their parents. Most commercial varieties of plant are a cross between a number of varieties bred for specific aims and will not reproduce.

The demand for heirloom seeds has been growing substantially in recent years as gardeners and small farmers seek better tasting varieties of vegetables, particularly tomatoes. The unique flavours and qualities of heirloom varieties has spawned a whole backyard research industry experimenting with these old traditional varieties. Seed saver networks and seed exchange events now occur on most continents.

Why are heirloom seeds important?

Most sensible people can recognise the importance of a small farmer in a developing country being able to grow his crop and save some of the crop as seed stock for the following year.

For subsistence farmers in the third world this is often all that keeps them on their land. These seed are passed down from generation to generation, shared between communities and produce plants that are often very well regionally adapted.

(organiccatalogue.com)

Thus farmers maintaining their own seed stock fit well with the old adage, “give a man a fish and feed him for day, teach a man to fish and feed him forever.” This remains the central argument for promoting seed saving and protecting the rights of local people to have control over their own crops.

However, in recent years, as the effects of climate change become more accepted and more obvious, new arguments are emerging identifying heirloom varieties as crops that have stood the test of time, often over many generations, and through weather changes and extremes that have occurred in the past. The resilience of these varieties to a multitude of environmental factors is of particular importance when adapting crops to the climate changes expected in the future.

In recent years, unseasonable spring weather in the US has devastated apple crops with some states loosing over 80% of their crop. Droughts in Africa and the Middle East have created millions of refugees. Weather changes are also being considered as contributory factors for the fungal disease presently decimating olive and fruit orchards across Spain and Italy. Responding to climate change events will require adaptation and reorganisation of plant production. It is fair to say heirloom varieties may have an important role to play in this.

Who should decide?

On 11 March 2014 the Parliament of the European Union rejected Commission proposals for a new Plant Reproductive Materials Regulation. The Commission is now expected to present a redrafted version in 2016.

Credit: landworkersalliance.org.uk

This rejected proposal, drafted in consultation with “technical experts” supplied by multinational corporations, sought to create criteria for “distinct, uniform and stable” varieties of homogeneous seeds. Under the proposed legislation it would be illegal to grow, reproduce, or trade any vegetable seed or tree that has not been been tested and approved by a national government and the “EU Plant Variety Agency.” Basically, this copyrighting of plant material only protects large companies.

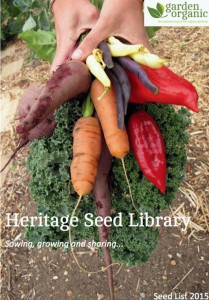

Opposition to this legislation was orchestrated across Europe by organisations such as the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements, the Campaign for Seed-Sovereignty and the UK Soil Association. The UK’s Henry Doubleday Research Association, now known as Garden Organic, responded by setting up the Heritage Seed Library to preserve seeds of as many of the older cultivars as possible. At present these organisations are awaiting the redrafted Commission proposals in 2016.

(ifoam.bio)

(seed-sovereignty.org)

(soilassociation.org)

(gardenorganic.org.uk)

(gardenorganic.org.uk)

How do I do it?

Saving seed is easy. Tomatoes, beans and peppers are ideal because these plants have flowers that are self-pollinating and seeds that require little or no special treatment before storage. Cucumbers, squash and gourds are more complicated because they can all be cross-pollinated by insects.

With tomatoes, the plants are nurtured to full maturity and the ripe fruit removed. The seeds and gel are scooped out and put in a jar of water (the rest of the tomato is eaten). The jar is then kept for about 5 days, shaken daily until the seeds sink to the bottom. The seeds are then removed and rinsed before drying on kitchen roll. Once dried they are stored in a dry condition in paper bags or containers.

Beans are even easier. Leave the beans on the plant until they are dried out and remove for storage. The seeds can be retained in the pods or removed for storage. Similarly with peppers, the pepper is left on the plant to dry out then removed and the seeds scraped out.

This simple practice of saving seed has been going for thousands of years. It requires many thousands of pairs of hands to keep heirloom species alive and continuing for the future. It would be a tragedy if this is restricted or prevented in our generation for the sake of corporate profits.